![]()

| bode'wadmimo speak Potawatomi nIshnabe'k The People mzenegenek books |

nizhokmake'wen resources/help Home Page: news & updates BWAKA - about us |

|

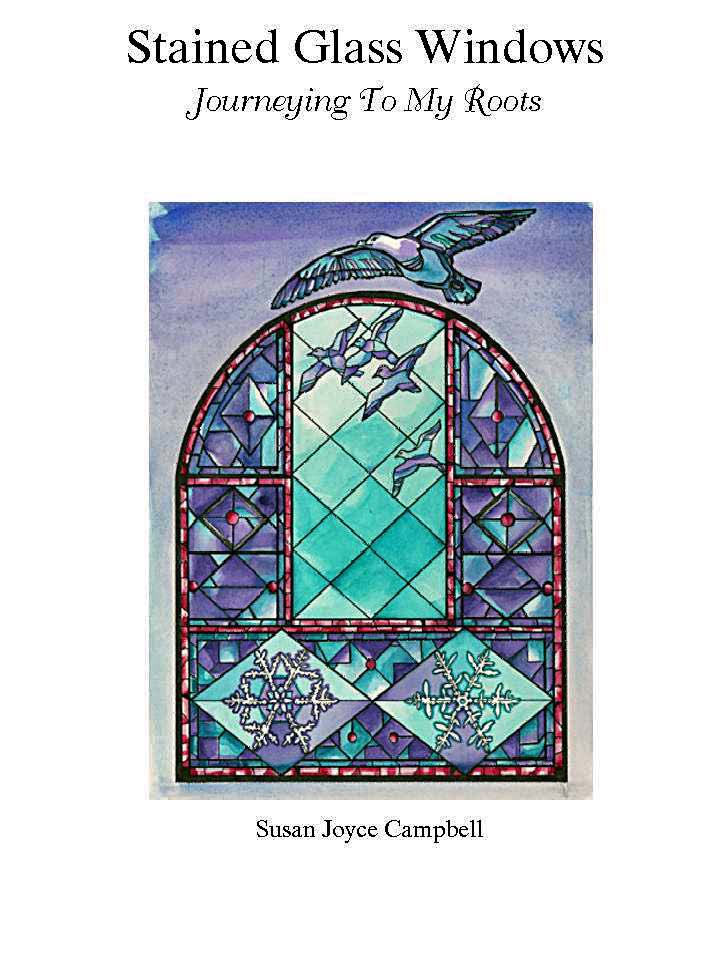

Update, July 2008: Susan's first book of poetry, a 60-page chapbook, has been published. The book is titled Stained Glass Windows. It is a compilation of mostly American Indian (Potawatomi) poems, with some non-denominational Christian poetry, and includes "Cage Nokmisen" and "She Who Prays...Always."To order, send a check for $12 (includes postage) to: Susan Campbell, 3200-C Wawae Road, Kalaheo, HI 96741. Or contact her at: nokmis.campbell@gmail.com Here are three of Susan's poems: |

|

|

|

* Rev. Thomas H. Kinsella. History of Our Cradle Land (Kansas City: Casey Printing Co., 1921) 19. |

| bode'wadmimo speak Potawatomi nIshnabe'k The People mzenegenek books |

nizhokmake'wen resources/help Home Page: news & updates BWAKA - about us |